by Mary Ann Moore | May 17, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

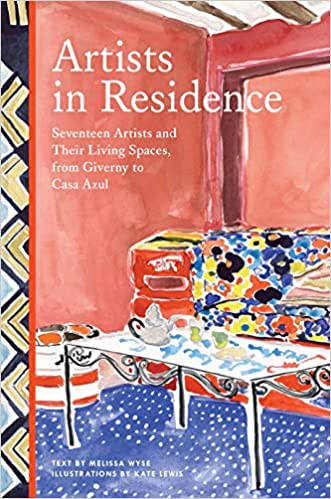

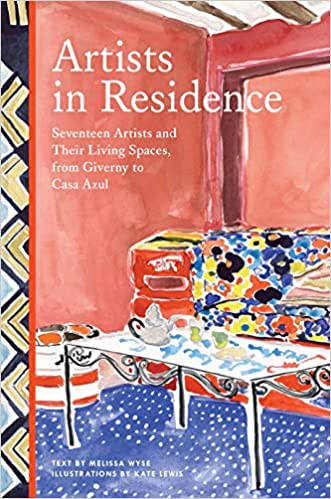

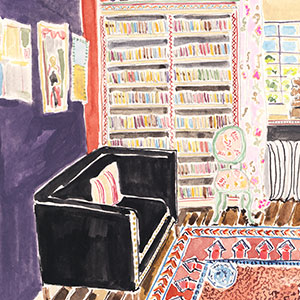

Artists in Residence (Chronicle Books, 2021) is a book that features the homes of seventeen artists “and their living spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul.” I really appreciate Melissa Wyse’s writing with her enthusiasm for and fresh approach to her subjects. And the illustrations by Kate Lewis are delightful and enticing.

Melissa Wyse is an art writer, fiction writer, and essayist who lives in Brooklyn, New York. Kate Lewis is an artist whose paintings are in private collections around the world. She lives in Chicago. The two met in the summer of 2017 at the Ragdale Foundation and their continued connection, some serendipity, and a “strange alchemy” led to this engaging book. Melissa and Kate encourage readers to follow their own curiosities.

As their introduction says, “Some of the artists in this book used their homes as places where they explored materials, staged still lifes, or inhabited the aesthetic vocabularies that would inform their artistic production. Others experienced their homes as sites of divergence, places where they stepped away from the hallmarks of their artistic work to embrace radically different colors, patterns, or aesthetic experiences.”

I do love that term “aesthetic vocabularies”!

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ”

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ”

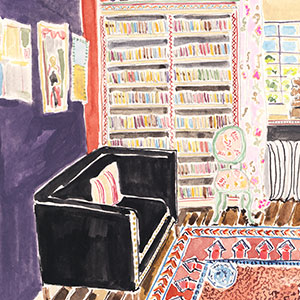

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and moved to New York City in 1938. “She worked as an artist for over seven decades, right until her death in 2010 at the age of ninety-eight.”

Bourgeois’ townhouse on West 20th Street was cluttered with stacks of paper, photos and articles pinned to the wall and English and French phrases as well as phone numbers written above her mantel. I appreciate Melissa’s take on the clutter:

“In our culture, with its stigmas against clutter and holding on to too much, we ignore the generative capacity of collecting and stacking up, all the pain and protection accumulation can hold. It can become a fortressing that keeps us safe – and a repository. All those books and papers allowed Bourgeois to live encompassed by the material traces of the past. Her archiving connected her with the seeds of memory that were such essential sources for her art.”

After her husband died in 1962 and after their three sons had grown, Bourgeois rearranged the rooms in her house, expanding her basement studio space into the ground floor living spaces. On Sundays she would open her home and host salons attended by various members of the community and especially “younger, emerging artists.”

Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation.

Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation.

The cover of the book, on the left, has an illustration of Hassan Hajjaj’s home in Marrakech, Morocco which serves as his private home and studio: Riad Yima where there is also a tearoom and boutique.

Clementine Hunter’s house on the Melrose Plantation in Louisiana is preserved by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Natchitoches.

Hunter’s home was owned by her employer for whom she worked as a servant in the plantation house starting when she was fifty years old. Before that, she had worked for decades as a field hand. She salvaged leftover paints from the artists who stayed at Melrose, painting scenes from life on the plantation and the surrounding community.

Her work was exhibited in gallery shows and Hunter “often sold her paintings herself from her home’s screened front porch.” In 1977, the Melrose Plantation was sold and the Cane River flooded, “sending water under Hunter’s house.” She moved into a house trailer at the age of ninety.

The old tin-roofed cabin was moved to the heart of the plantation grounds where it has been preserved and visitors can take a tour. The whole house hasn’t been preserved though. As Melissa points out, it’s “strangely pulled apart; the kitchen and the bathroom shorn off the back of the building, the wall paper removed, the linoleum peeled off , the house stripped down to its floorboards and wood wall planks.”

Melissa goes on to say about the preservation: “It blurs the temporal realities of her life and denies the specifics of her experience . . . In an area dotted with restored plantation houses, in a country that continues to enact its racism in overt and subtle ways, Hunter’s stripped-down house feels symptomatic of a larger problem in how we tell and what we omit from history.”

Clementine Hunter would wallpaper her walls and onto the ceiling. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, at their home in Charleston, East Sussex, England, painted on all its surfaces including walls, mantels, doors and doorframes, and furniture.

If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.”

If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.”

Duncan Grant had several romantic relationships with men and with Vanessa Bell with whom he had a daughter Angelica in 1918. After their physical relationship ended, Bell and Grant remained close friends and lived together for most of their lives. “At Charleston, they enjoyed a harmonious and egalitarian approach to domestic living.”

As directors of Omega, an artists’ design collective, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant “crafted a philosophical framework that informed their approach to their own home at Charleston. They saw their rigorous practice of painting their home’s surfaces as a part of, and equal to, their artistic expression elsewhere . . . at Omega they had asserted the idea that decorative arts and interior decoration possessed intrinsic artistic value. In keeping with this philosophy, they transformed Charleston into a house-sized painting, a piece of art in its own right.”

Theirs was not a “traditional domestic experience” and Bell and Grant “painted an entirely new way to experience the space of home.”

And wouldn’t it be good if we aspired to the qualities Melissa describes of the Bell-Grant home, in our own homes: ““The inventiveness of their interior decoration mirrored the environment they fostered for the people within it: one that embraced tolerance, open-mindedness, creative and intellectual engagement, and personal freedom.”

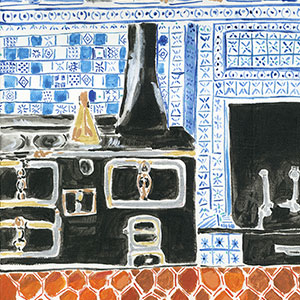

Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.”

Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.”

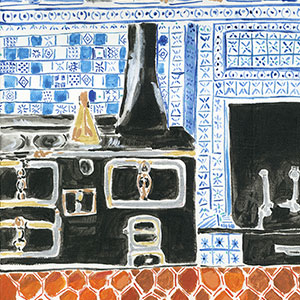

One of the illustrations in the Claude Monet chapter of the book is the yellow dining room where nearly everything is painted yellow. “Yellow even checkers the brightly tiled floor.” The illustration to the left is of the “enormous oven” in the kitchen where the walls are blue and tiled “with a constellation of organic blue and white starbursts and fleur-de-lis patterns.”

“When I think about Monet’s house at Giverny,” Melissa writes, “I think about how it feels to be submerged in color and space. His home aligns with my sense that aesthetic choices can be not just decorative, but also experiential, and that our experience of interior spaces can shape the way we feel. And while Monet’s interiors didn’t adopt his art’s content or style they do share his heightened awareness of color’s impact . . . In his home, he stepped easily between two worlds: the gardens that served as his core artistic subject and inspiration and the centering aesthetic experience of his house’s interiors.”

If I ever travel to Mexico City, I’ll certainly want to see the homes of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. There is the Kahlo home, Casa Azul, in Coyoacan, on the outskirts of Mexico City, and the two adjoining houses Rivera had built for himself and Kahlo in the San Angel neighbourhood of Mexico City.

“As her physical health worsened, Kahlo’s home became even more important for her as a source of creative stimulation and engagement,“ Melissa writes. The kitchen at Casa Azul has yellow floors and table with the lower portion of the walls painted bright blue. Most of the kitchenware is visible along with wooden spoons on the wall and painted pottery dishes on open shelves.

“Kahlo’s home feels like a distinct work of art, separate from her paintings. It has its own vocabulary of shape and form, color and line, its own aesthetic preoccupations and interests. It serves its own purpose, not as a staging ground or sketch or backdrop for her art.”

Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch painter, in May 1889, “voluntarily admitted himself to Saint Paul de Mausole, a psychiatric asylum in Saint-Remy, France. His former home in Arles, France and his room at the Saint-Remy asylum “served as places in which to paint and also as subjects of his paintings.”

Melissa says of Van Gogh: “He did not create his art in the thrall of mental illness; during and immediately after episodes, he was unable to create at all. He created his immense body of work through the diligent daily painting practice he adopted during the lucid months between attacks, when he saw his creative work as a way to maintain his sanity, to save his mind, to keep some traction on his own well-being.”

Other artists in the collection include Donald Judd, Claude Monet, Less Krasner & Jackson Pollock, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Zaria Forman and Henri Matisse.

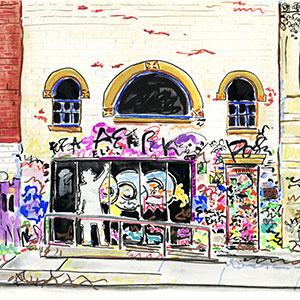

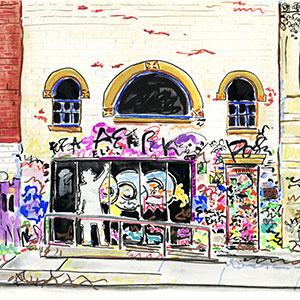

It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

Visitors are not able to visit Basquiat’s former home but admirers do travel on pilgrimages to 57 Great Jones Street and have left graffiti on the outside of the building. “It is an evolving, unofficial exhibit – the outside walls of his home transmuted into a living site of art.” There is also a plaque for Basquiat installed by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

“Sometimes houses are preserved. Sometimes they endure,” Melissa says.

I can understand how Melissa Wyse and Kate Lewis felt a “new intimacy with the creative life of each artist” as they visited, painted, wrote about, imagined the homes of the visual artists included in Artists in Residence. Readers get to experience that too. I think we’re always fascinated to see where artists and writers create their work, how their homes influenced and supported their work and how their homes so often were and are living works of art.

Excerpted from Artists in Residence: Seventeen Artists and Their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul Hardcover © 2021 by author Melissa Wyse and Illustrator Kate Lewis. Reproduced by permission of Chronicle Books. All rights reserved.

by Mary Ann Moore | May 1, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

Patrick Lane often greeted poets in the reception area of Honeymoon Bay Lodge on Lake Cowichan, Vancouver Island, when he led poetry retreats there. He’d also help carry our luggage to our rooms. I was remembering that about Patrick, who died in March 2019, when I went to a retreat with Lorna Crozier earlier in April 2022.

Patrick Lane was born in Nelson, B.C. in 1939 and grew up in the Kootenay and Okanagan regions of the BC interior, primarily in Vernon. He won nearly every literary prize in Canada, received several honorary degrees, and in 2014 became an Officer of the Order of Canada.

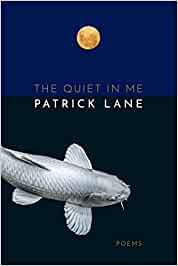

When Lorna did a reading on one of the evenings at the retreat in April, she had a few of us read poems from Patrick’s posthumous collection, The Quiet in Me, which she compiled following his death.

When Lorna did a reading on one of the evenings at the retreat in April, she had a few of us read poems from Patrick’s posthumous collection, The Quiet in Me, which she compiled following his death.

Lorna said when putting the poems together for the book, she chose the first and last poems and then figured out, by putting them on the living room floor, which poems belonged beside one another in the collection. It was an intuitive process as she chose poems “that want to slide between the sheets together.”

The first poem in the book is “Living in a Phantom Hut” which begins: “A wolf-hair brush in a yellow jar, a pool at dawn, / Basho on the road to the deep north.”

The speaker in the poem reflects on the Japanese haiku master Basho and notes the Barriere River, one of the main tributaries of the Fraser River in British Columbia. The classic poets and northern B.C. were significant to Patrick’s life and his poetry. And Basho is the name of one of his cats still living as far as I know. (Basho was eighteen in 2017 which is the year noted at the beginning of Lorna’s memoir Through the Garden: A Love Story (with Cats).)

Each line of “Living in a Phantom Hut” says so much about the end of one’s life and the peace that may be found there. “Old misfortunes can bring an old man peace,” the narrator says.

“There is nowhere I can go where I haven’t been” is the second to last line. The poem closes with “when I hold the brush to my ear I hear the moon,” referring back to the master poet Basho.

In the copy of Patrick’s memoir, There is a Season, that he inscribed for me, he has written an inscription to include the last half of a Basho haiku: “We are all the bamboo’s children in the end.”

In the last poem of The Quiet in Me, “Fragments,” the speaker is referring to “woodshed litter, / bits of bark and dust, fragments of fir and hemlock” and then, in the heart of the poem: “a barefoot child lights a fold of paper.”

“Seventy-three years will come to add to his seven,” the speaker says of the boy and he wonders what he can tell him.

In her introduction to The Quiet in Me, Lorna wrote about Patrick’s love of “the creatures and flora of the world.” She said, “as he lay dying, he ached not for himself but for the loss of caribou and whales and owls and salmon. He bemoaned the clearcuts and the forests burning in his home province.”

Patrick wrote of hummingbirds, “bees and the fat birds calling,” cherry blossoms, elephant seals, geese and beetles and eagles mating. A special tree for him was “The Elder Tree” where, as he wrote, “ I come to pray.”

The narrator notes the turtle that “rose/ from the pond’s heavy dark to heal her winter shell” and remembers his father planting trees. “How long ago the fathers, their stories another kind of cure.”

The Quiet in Me was launched on Zoom on April 22, 2022, with Patrick’s long time friend and publisher, Howard White, hosting. The event was organized by ZG Stories and sponsored by Munro’s Books in Victoria.

Friends of Patrick’s read poems and Rhonda Ganz, designer of the magnificent cover of the book, read “The Elder Tree.” She said “I wouldn’t be a poet if it weren’t for Patrick Lane . . . “ She mentioned Lorna Crozier too, with gratitude. Rhonda knew about the particular tree in the poem and Patrick did set out to show her where it was one day but then changed his mind.

Patrick Lane was one of hundreds of writers Howard White published at Harbour Publishing he said in his opening remarks. Howie knew “more of the guy he hung out with” than the poet who he first met in 1974 or thereabouts. He remembers going to the Cecil Hotel bar in Vancouver (demolished in 2011) after one of Patrick’s readings.

Pat, as he was known in those days, moved to Pender Harbour with his partner Carol. Howie and Patrick shot pool, drank together and “got be good friends.” Pat was an easy going guy, Howie said, and an enthusiastic storyteller.

Patrick apparently made some money as a handyman, “slamming together some rough back steps.” After a few years he was building houses. He “packed in the cozy scene in Pender and went on the road again,” Howie said. “Poetry was Patrick’s battleground.”

When I attended poetry retreats with Patrick, I don’t remember him saying: “If you’re going to write, there can’t be a safety net.” That’s what Howie remembers Patrick saying and I appreciate hearing it now. It doesn’t mean he didn’t make money in ways other than publishing his poetry but when he heard that someone he knew was going to get a law degree to support their writing financially, he said, “That’s bullshit.”

Steven Price was nineteen when he met Patrick Lane at the University of Victoria. At that time, Steven thought poetry had to rhyme. He said of Patrick: “He terrified me and electrified me.”

Patrick became a mentor and a friend to Steven who said Patrick Lane was one of the finest human begins he’s ever known. Steven read “Slick” which contains the line: “How hard it is to remember I forget, to forget I remember.” Patrick describes a knife blade as “a sigh, a trout caught in the mountains,/ the flight of willow leaves.”

He was a master of metaphor and a master teacher. So often with we poets at retreats, Patrick would suggest taking out the first few lines of a poem we had written. Or a whole stanza. If we happened to sit with him in the late afternoon, he’d have the typed version in front of him and would draw a pen through the first lines, draw arrows where other lines ought to go and take out most “ofs” and “ands.” At times he had us counting syllables and he always had us listening to the cadence and rhythm of a poem. Our ordinary speech is full of poetry Patrick said. No one talks in sentences.

Esi Edugyan said Patrick was her first teacher when she was seventeen at the University of Victoria. She remembered that in her second year her mother had suddenly passed away and Patrick gave her a bear hug. Esi read “Icebergs off Fogo Island.”

It is the quiet we love, the way water touches us,

the iceberg an animal gone astray in search of time.

The poet reminds us: “The water that is ice is ten thousand years old.”

One of Patrick’s sons, Michael Lane who was born in Vernon, B.C. and lived in Pender Harbour as a young child, chose “Om” to read as he felt it was his father in his final days.

I feel my brittle bones and smile. I am as fragile as winter grass.

I think of leaping to the floor and don’t.

Like my old cat I climb down slowly, accept

the smile of my woman who gives me coffee in the morning.

From “Om” by Patrick Lane

It’s such a gorgeous poem with a mole’s cry, memories of “when we moved / naked in a summer far away” and the Buddhist writing that was a literary influence: “and so the prince set out on the road to discover suffering / and gave his self up at the last.”

Esi Edugyan and Steven Price are both writers and partners and Steven commented on the example of Patrick and Lorna who “believed in each other.”

Patrick’s son, Richard Lane, said his relationship with his dad “didn’t stretch too deeply into poetry.” They spoke about trucks, football and hammers. Patrick’s choice was hammering by hand not with a pneumatic hammer. They talked of hummingbirds a lot so Richard read “Hummingbirds,” the second poem in The Quiet in Me.

Richard also read an except from “Wild Birds” written in the seventies and included in The Collected Poems of Patrick Lane (Harbour Publishing, 2011).

Because the light has paled and the moon

has wandered west and left the night

to the receding sea, we turn into ourselves

and count our solitudes. The change

we might have wished for had we time

To wish is gone. . . .

From “Wild Birds” by Patrick Lane

Later at the Zoom launch, Richard said he could hear his father’s voice in his poetry.

Lorna Crozier said he loved “all of you who are reading tonight.” For the people reading, Patrick was their first teacher. In a way, she said, she had to “channel” Patrick to make a change, delete a poem, add a poem” for The Quiet in Me.

In an article in the Toronto Star (Sat. April 9, 2020, “Celebrating a life of poetry together”), the Books Editor, Deborah Dundas, recounts a conversation she had with Lorna via telephone. Although he had been ill for three years, an illness that went undiagnosed, Lorna said, in the article” “Neither of us knew he was dying.”

In the introduction to The Quiet in Me, Lorna writes: “His calling to poetry began when he was a young man working in the mill towns of British Columbia, and it never left him. About a month before he died, he gave me a folder of poems he’d been working on in the rare moments of grace he found in the midst of an enervating illness. ‘Take a look,’ he said. ‘I think I have a small book here.’ I thought so, too, and as we always did for one another, I made a few editing notes on the pages. He never felt well enough to return to these poems and though most of my comments consisted of one word, ‘Wonderful,” it fell to me after his death to pull the manuscript together and make the final cuts and edits.”

“My heart is close to breaking,” Lorna said following the reading of Patrick’s poems at the Zoom launch . She read “Kinttsugi” meaning “golden repair” which is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mixing lacquer with powdered gold. Lorna said Patrick’s “golden repair was poetry.” And she read “Carefully.”

Carefully

The mole in his small room

moves a small stone

and waits out the rain.

Patrick Lane, The Quiet in Me

Howie read the title poem of the book: “The Quiet in Me.” In the poem, the speaker lifts a man who has fallen to the pavement from his wheelchair and recalls a friend, from “long ago,” a prospector he had lifted to his bed “and dead, / and dead.”

. . . . . . . . . . . the lovers too I laid to rest

in the sleep that follows love, all the arms I’ve held, such arms as will hold me.

from “The Quiet in Me” by Patrick Lane

Lorna wrote in the introduction to The Quiet in Me: “A poet who sang the darkness, he also found music for the enlightened moment in the garden, the turtle in the mud, the cat presenting to his master the body of a mole. In wonder and wisdom, he found the notes and language of love and the deep quiet that he came to in himself.”

As Lorna said at the Zoom launch, the god of Patrick’s understanding was an old tree. The Quiet in Me is dedicated to his children and grandchildren, his beloved students and his life-long friend and poetry publisher Howie White. I’m very grateful to have been one of those students.

Select poems excerpted from The Quiet in Me by Patrick Lane (Lorna Crozier, ed.) 2022, with permission from Harbour Publishing.

Things Will Come to You

The song your grandmother taught you,

the beautiful, the beautiful river

gather with the saints at the river, smooth stones

instruments of silence. Hold one to your temple.

Remember. Hear your true name. Moon, sea,

stone: always listen from the quiet part of you.

Mary Ann Moore

by Mary Ann Moore | Apr 15, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

“I feel unmoored when I’m not writing. Incomplete. Not quite myself.” Those are the words of Elise Valmorbida, author of The Happy Writing Book: Discovering the Positive Power of Creative Writing (Laurence King, 2021).

I definitely relate to what Valmorbida says above, included in her book that is the result of “decades of deliberation and discovery about the art, craft and positive experience of creative writing.”

Valmorbida, who grew up Italian in Australia and lives in London, has been a designer and creative director as well as the author of several books. She continues to teach Creative Writing through various organizations, at literary festivals and community-building organizations.

The Happy Writing Book (not designed by Valmorbida) has a very cheerful design with its orange cover and the large orange numbers that introduce each chapter.

In “Write What You Know?” Valmorbida says “your own experience will inform your work” but points out that authors do research. In the case of Annie Proulx, she “writes what she knows, but she didn’t know it before she started delving.” That delving sounds fun as Proulx “takes herself to new places, haunts little stores and buys heaps of second-hand books about farming, local history, auction records, hunting tackle, whatever. She transcribes wording from street signs and menus and advertising. She hangs about and absorbs conversations, noting the speech patterns, the vernacular, topics of concern.”

“Write to discover what you want to know, Valmorbida says. I like that approach and find it much more fascinating to learn as you go rather than to describe something you already know. Of course, you can write what you remember and approach it in an inventive way. There are many fine examples of doing that including a couple of memoirs I’ve read recently: Safekeeping by Abigail Thomas (considered a “fractured” memoir due to its short chapters written as vignettes from a life) and a more recent book, Persephone’s Children by Rowan McCandless (considered a “mosaic” memoir with the various forms of personal essays used by the author).

In a chapter about procrastination, Valmorbida suggests joining a class or making a circle. Circles can take different forms such as one to share work and get some feedback on your work from fellow writers. (Thank you Easy Writers with whom I worked for years.) You can form a circle where you get together to write and share your work, focusing on what most resonates with each listener. If you need some confidence building and aren’t out for impressing publishers, this is the way to go. (This is the approach taken in the Writing Life women’s writing circles I lead.)

In her chapter entitled, “Keep A Diary,” Valmorbida says “Don’t attempt to write out your entire day, every day.” I do, especially lately, as it’s a grounding exercise for me. I like her suggestion though of choosing a theme – “just one strand of experience – say, the music you’ve been listening to, where and how you heard it, what effects it has on you. Or you could focus on the places you’ve been to, physically and imaginatively, and see what thoughts take shape in your writing.”

That approach sounds like you could end up with some prose poems or short pieces of life writing that describe a year in your life. Recently I picked up a copy of The Book of Delights by Ross Gay in which in wrote about delights or “small joys we often overlook” each day for a year beginning with his 42nd birthday.

Valmormida says: “If you do only one thing in the diary department, I urge you to try your hand at this: gratitude. Make a regular record of the day’s blessings: a pleasure experience, a kind gesture, an accomplishment, a loved one, a smile, a gift, a moment of beauty.”

It’s a grand way to sleep at night “with a smile in your mind, and your dormant body will be suffused with benevolence.”

Studies show that, over time, this positive writing ritual can lower stress and anxiety levels, while boosting self-confidence, clarity of thought and resilience. In other words, you could be writing yourself happy.”

While publication can be a thrill, Valmorda says, “If you want to be published, you’ll be happier if your desire to write is greater than your desire to be published.”

I agree with that. “The point is to write,” Valmorida says. “The joy is in the doing. Discovering yourself, word by word. Unearthing ideas, word by word. Try creating without regard to result. Enjoy the process, how the practice of writing subtly makes its way into how you’re living. Your writing, like your life, is a work in progress.”

And you can always re-envision a situation as you write. In her chapter entitled “Invent an Alternative Present,” Valmorbida says: “You can rewrite the present with the hope of making things better. And – who knows ? – such action may even succeed in making things better.“

I believe that what we write can draw situations to us. Writing can be powerful. People have said they wrote in their journals about situations they’d like to improve and without realizing until some time later, they drew to themselves the home, the relationship, the job they were desiring. There’s also prescience in writing so that we write about a situation long before it comes to pass. I even did that in a collage (done in about 2015) with an image of a house that looks very much like the one we live in now.

Valmorbida says in her chapter, “Write the Future,” that John Updike “commented on the frequently prophetic quality of his fiction, to the point where people would appear in his life who’d started out as fictional characters. Reality eventually acts out our imaginings: when we write, we do so out of latency, not just memory.”

A good suggestion in the book is to write out the negative and positive. The “negative” could be the emotions related to traumatic events. Valmorbida notes the work of James Pennebaker who investigated the effects of “expressive writing” and found that it led to an improvement in various physical symptoms and immune function. So writing about your “deepest thoughts and feelings can lead to better health – and notably fewer visits to the doctor.”

As Valmorbida says, writing about negative experiences or “vexing” people “doesn’t take the vexations away, but it does take away some of the sting.”

Virginia Woolf, in her autobiographical essay, “A Sketch of the Past,” referring to a “shock,” wrote: “It is only by putting it into words that I make it whole; this wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me; it gives me, perhaps because by doing so I take away the pain, a great delight to put the severed parts together. Perhaps this is the strongest pleasure known to me. It is the rapture I get when in writing I seem to be discovering what belongs to what; making a scene come right; making a character come together.”

Woolf has connected the pleasures of writing therapeutically and writing artistically. Valborbida says of her own fiction writing that while writing her last novel, “I felt a general sense of satisfaction, commitment and purpose, a quiet inner anchoring – even during difficult times.”

I appreciate the term “inner anchoring” which I find applies to writing in a journal every day and in writing a poem about what one observes in the moment.

Elise Valmorbida says “Be interested in everything, Read everything. Learn something from everything.”

Number 100 in her book is “Write Now.” “ Now is the beginning of the future. The quality of your now affects the quality of all your future nows. Now is the most important time of all.”

by Mary Ann Moore | Mar 25, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

I asked the women in the Writing Life circle, what’s in the middle? It was the first writing circle of a six-week series with the theme of “Piecing Our Stories from Life.” I had quilts in mind when I came up with the theme of “piecing” and quilts always start in the middle.

The women in the Writing Life circle have written together, in the past, for weeks and some for years. I wondered what they thought was in the middle of the writing they had done in the past. What did they think was a recurring theme.

As I write along with the other writers, I thought of the “middle” of my own writing. It’s interesting to approach the question by answering it in the third person as then you can have some distance and some insight about this particular writer whose work you have read (who just happens to be you).

I wrote: Mary Ann Moore writes about peonies in her grandparents’ garden, her first grade school teacher, a fresh radish from the vegetable patch. It’s life’s ordinary pleasures that appear to bring her joy. Even while travelling in Greece or Turkey, Mary Ann notes the oregano on feta, a circle of women telling stories. There is a spiritual aspect – the muezzin’s call to prayer, the sanctity of the Hagia Sophia, the sarcophagus of the poet Rumi with its gold Arabic calligraphy. [Photo of crewel work by my mother, Billie, with cover of poem called “Women’s Hands.”]

I wrote: Mary Ann Moore writes about peonies in her grandparents’ garden, her first grade school teacher, a fresh radish from the vegetable patch. It’s life’s ordinary pleasures that appear to bring her joy. Even while travelling in Greece or Turkey, Mary Ann notes the oregano on feta, a circle of women telling stories. There is a spiritual aspect – the muezzin’s call to prayer, the sanctity of the Hagia Sophia, the sarcophagus of the poet Rumi with its gold Arabic calligraphy. [Photo of crewel work by my mother, Billie, with cover of poem called “Women’s Hands.”]

Planting seeds in the field of a Turkish eco-farm takes her back to sitting by the cucumber patch with her grandfather, his cutting of a fresh cucumber slice with his pocket knife.

Mary Ann links the Ottawa Valley to Turkey and includes the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo at times perhaps for her determination to create despite the physical odds against her. Or it may have been her painting that kept Kahlo alive and Mary Ann reflects on the creativity of women with her grandmother’s quilt, her crocheted doilies and the work of other women whether in a traditional Greek cloth bag woven in patterns of red or a killim created by village women. [Photo of cloth bags made with images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Frida Kahlo.]

Mary Ann links the Ottawa Valley to Turkey and includes the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo at times perhaps for her determination to create despite the physical odds against her. Or it may have been her painting that kept Kahlo alive and Mary Ann reflects on the creativity of women with her grandmother’s quilt, her crocheted doilies and the work of other women whether in a traditional Greek cloth bag woven in patterns of red or a killim created by village women. [Photo of cloth bags made with images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Frida Kahlo.]

The fact that certain languages don’t have a word for “art” fascinates Mary Ann and is at the middle of her explorations.

The people of ancient Crete made pithos jars to hold olive oil, decorated them with carved flowers and leaves.

In a jam jar on the oil cloth covered kitchen table of her childhood was a bouquet of buttercups and daisies.

The beauty of everyday objects, her relationship with the plant world and to her ancestors, connects this writer to a magnificent spiritual system. [Photo of detail of Turkish, hand painted plate.]

The beauty of everyday objects, her relationship with the plant world and to her ancestors, connects this writer to a magnificent spiritual system. [Photo of detail of Turkish, hand painted plate.]

Does the “spiritual system” have a name?

God?

Goddess?

Tea cup?

Peony?

Prayer?

by Mary Ann Moore | Mar 15, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

It’s spring here on Vancouver Island with crocus, daffodils, primulas, hellebores and other colourful flowers in bloom. Winter was a challenge as we had more snow than usual (and we’re not prepared for that out here) and Sarah and I learned in December that the house in which we’d rented the upper level for seventeen years was being sold.

It’s spring here on Vancouver Island with crocus, daffodils, primulas, hellebores and other colourful flowers in bloom. Winter was a challenge as we had more snow than usual (and we’re not prepared for that out here) and Sarah and I learned in December that the house in which we’d rented the upper level for seventeen years was being sold.

Packing is tiresome on its own and to that, I decided to go through everything, letting go of books, many journals, notes, and other papers filling files. There are still photo albums to pare down which I’ve inherited from my great aunt, aunt and uncle, and father. I’m now at the stage of putting things away in a beautiful home, also a rental and all to ourselves, about fifteen minutes south of Nanaimo. [The photo shows the end of the house where Sarah has her studio and she and our younger cat, Izzy, can go out on the deck.]

Sarah and I are very grateful to have found such an amazing place. We thought we had to seriously “downsize” and this place is bigger. We’re appreciating the quiet of being out in the country and the space around us. We’re on five acres along with the owners’ house and we’re feeling expansive in various ways. We’re also feeling the challenges of an adjustment and look forward to the days when our surroundings feel comfortable and familiar. It’s getting like that more and more every day. (We’ve been here two weeks now.)

As I unpacked the linen closet items, I came across a quilt my grandmother made with other quilters in the 1950s. They sat around a quilting frame, sharing stories as they pieced and stitched.

As I unpacked the linen closet items, I came across a quilt my grandmother made with other quilters in the 1950s. They sat around a quilting frame, sharing stories as they pieced and stitched.

The quilts became stories too as fabric, ribbon, and other fragments turned into works of art and of practicality. The pieces creating the pattern of hearts in my grandmother’s quilt are from her cotton housedresses, already faded. The backing is made of bleached flour sacks. I have always loved quilts and this particular one is full of the memories of my early life with my grandparents in Eganville, in the Ottawa Valley, Ontario. I expect I used it on my bed when I was a kid and here we are sixty-five or so years later.

The women quilters were “piecing” which is similar to what we do when we write, stitching scenes from memory that may become part of a larger work. I think it is a good metaphor for the next six-week Writing Life circle which will begin on Wednesday, March 23. We’ll gather in person at my home in Nanaimo as if around the quilting frame, in a circle to write and share with the theme of “Piecing Our Stories From Life.” You’ll find further info here.

Writing was the healing place where I could collect the bits and pieces, where I could put them together again. It was the sanctuary, the safe place.

from Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work by bell hooks (1952 – 2021)

As several of us have discovered, we can connect to one another by sharing our stories by email. For those of you not able to attend a Nanaimo writing circle, I’m offering a circle “from away” via email called “Our Stories and How They Connect Us.” It begins Thursday, March 24.

As several of us have discovered, we can connect to one another by sharing our stories by email. For those of you not able to attend a Nanaimo writing circle, I’m offering a circle “from away” via email called “Our Stories and How They Connect Us.” It begins Thursday, March 24.

For some, it’s actually more comfortable to express themselves through the written word only. You may have discovered that through writing letters to someone and finding out more about yourself and your pen pal as you do so. Several women were part of the circle “from away” in the past and I hope we can rekindle those connections. You’ll find more information here.

On occasion, I’ll offer individual writing circles via Zoom. Back in the spring of 2020, I didn’t think offering women’s writing circles via Zoom would work or offer the same depth of writing and sharing experience. As it turns out, Zoom has been a very helpful partner in offering circles so that we can stay connected by following the same guidelines we follow in the in-person circles.

I wish you a Happy Spring, clearing away what no longer serves you which may include, as the days go by, an easing of restrictions imposed during the pandemic. Think of the babies and toddlers who won’t have seen many faces and will now be able to see us un-masked. So many stories to share of our experiences of the last two years, the hardships, disappointments and the many gifts.

by Mary Ann Moore | Feb 27, 2022 | A Poet's Nanaimo

Sarah and I have never lived anywhere for seventeen years, in the same house that is, together or apart, before the house in which we’ve lived in Nanaimo.

Now we’re on the move to another home in Nanaimo, about fifteen minutes south of downtown, and I’m thinking of all I’m appreciating about our current home – for just one more day.

We arrived in Nanaimo, B.C. from Guelph, Ontario with our four cats in May of 2005. We had a few suitcases with us but that was it until our furniture and other belongings arrived about a week later. Life was very simple with so few belongings. Our landlord Peter loaned us laundry baskets full of linens, a mattress, a lamp, dishes and cutlery. I can’t imagine now being without my computer for a week! Sarah painted the bedrooms and we’d take little jaunts out to get to know our new city. Neck Point, just seven minutes from our home, was a favourite spot where we looked towards the Sunshine Coast of the mainland.

We arrived in Nanaimo, B.C. from Guelph, Ontario with our four cats in May of 2005. We had a few suitcases with us but that was it until our furniture and other belongings arrived about a week later. Life was very simple with so few belongings. Our landlord Peter loaned us laundry baskets full of linens, a mattress, a lamp, dishes and cutlery. I can’t imagine now being without my computer for a week! Sarah painted the bedrooms and we’d take little jaunts out to get to know our new city. Neck Point, just seven minutes from our home, was a favourite spot where we looked towards the Sunshine Coast of the mainland.

Our rental was to be temporary as we looked for a house to buy. I don’t remember ever looking for a house once we landed here. Or perhaps, we did occasionally. We got very comfortable and were treated very well in our rental home.

Our rent was affordable. Buying a house with its upkeep would mean “jobs” and why spend time elsewhere to buy a house that you can’t spend much time in? We stayed with our art making and graphic design, in Sarah’s case, and freelance writing, poetry and writing circles, in mine. Besides, Peter has been a landlord extraordinaire. He continued to work in his wonderful garden that is terraced with three ponds and a waterfall. The vista from our living room is of the Grandmother of All Surrounding Mountains, Te’tuxwtun to the Snuneymuxw people, and the mountains south of Nanaimo. We could watch the phases of the moon and the many aspects of the sky throughout the day and evening. In our front courtyard, we could sit under the mulberry tree and hazelnut, chatting with friends perhaps.

Peter liked to dry herbs from his garden, make tomato juice, salsa, and strawberry jam and share his prime rib roast with us. We were never without surprise treats of dinner or lunch. Oh, and there was Christmas with spiced nuts and bolts, shortbread cookies, butter tarts and a turkey dinner if he happened not to be in Mexico. (We had our last Christmas dinner in December 2021.)

If ever we ran out of anything, the stores were close but Peter’s pantry was closer!

The four cats we brought with us have all died: Miss Pooh, Kadi, Simon and Qwinn. We’re leaving their ashes here, in the Zen garden at the top of the driveway, and their spirits are always with us so they’ll be coming along to our new home in the country. And we’ll be taking Squeaker and Izzy with us, both very much alive. And so far, weathering the transition very well.

The four cats we brought with us have all died: Miss Pooh, Kadi, Simon and Qwinn. We’re leaving their ashes here, in the Zen garden at the top of the driveway, and their spirits are always with us so they’ll be coming along to our new home in the country. And we’ll be taking Squeaker and Izzy with us, both very much alive. And so far, weathering the transition very well.

I wrote Writing Home: A Whole Life Practice here and Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey was made into a digital format. I published poetry in various publications including chapbook anthologies edited by Patrick Lane, my own chapbooks, and a full length book of poems (Fishing for Mermaids, Leaf Press, 2014).

Other writing was in the form of advertorials for the Nanaimo Daily News, articles for More Living magazine and Synergy, book reviews for the Vancouver Sun and other publications.

I mention all these things as I’ve been going through files of clippings going back to the eighties. I do have some folios of articles I’ve written but those ancient files have been recycled. So many journals have been shredded as I ready myself to carry the memories although not in physical form. It’s time for a fresh new chapter for both Sarah and me.

It’s been wonderful to be part of a writing community on Vancouver Island. I started meeting writers right away when I attended the Victoria School of Writing and began going to poetry retreats with the late Patrick Lane. Connections made there with other poets have continued.

I appreciated WordStorm monthly poetry events in Nanaimo co-founded by David Fraser and Cindy Shantz. I joined a group with them and other writers, calling ourselves the Easy Writers. We had such fun going to Poetry Gabriola as a group meeting the likes of Robert Priest, Richard Van Camp, Ivan Coyote and Sheri-D Wilson.

I appreciated WordStorm monthly poetry events in Nanaimo co-founded by David Fraser and Cindy Shantz. I joined a group with them and other writers, calling ourselves the Easy Writers. We had such fun going to Poetry Gabriola as a group meeting the likes of Robert Priest, Richard Van Camp, Ivan Coyote and Sheri-D Wilson.

At home, I started offering women’s writing circles called Writing Life (a continuation of the Flying Mermaids circles I had offered in Ontario) and I held salons for friends who had new books: Laura Apol from Michigan, Arleen Pare from Victoria, Alison Watt from Protection Island, Diana Hayes from Salt Spring Island, and Leanne McIntosh from Nanaimo. I think I had a salon way back when for Tina Biello and we did other readings together as our poetry books had come out at the same time.

I made flower essences in the garden here starting with Rhododendron, the definition of which is Self-Trust. Spirit of the Island is the name of the flower essence series, a name Sarah and I came up with together. Another of the Spirit of the Island flower essences is Camellia: Be Here Now. It is a photo of the camellia that attracted our new landlord to read Sarah’s post re looking for a place to live.

I made flower essences in the garden here starting with Rhododendron, the definition of which is Self-Trust. Spirit of the Island is the name of the flower essence series, a name Sarah and I came up with together. Another of the Spirit of the Island flower essences is Camellia: Be Here Now. It is a photo of the camellia that attracted our new landlord to read Sarah’s post re looking for a place to live.

Since the house was sold in December (we’ve been renting the main level suite), we’ve been letting things go. We’ve made several trips to the Haven Society thrift store and to Well Read Books, Literacy Central’s bookstore. And I’ve given many books away to women in the circle circle. Still, there are many books to pack. We’re at a stage now that we want to take with us what will support our new phase. We’re not sure what that will look like but we’re grateful we have found a beautiful rental home in the country. Our new home will have lots of room including studio and office space, a garage and five acres on which to roam. The owners also have a house on the property. Annemarie is an avid gardener which is what attracted her to the camellia.

Thinking ahead to our new home has kept us going during these final days of packing as well as appreciating all we’ve enjoyed here.

A faded garden flag

empty flower pots

a tiny temple under the ferns

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ”

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ” Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation.

Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation. If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.”

If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.” Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.”

Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.” It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

When Lorna did a reading on one of the evenings at the retreat in April, she had a few of us read poems from Patrick’s posthumous collection, The Quiet in Me, which she compiled following his death.

When Lorna did a reading on one of the evenings at the retreat in April, she had a few of us read poems from Patrick’s posthumous collection, The Quiet in Me, which she compiled following his death.

I wrote: Mary Ann Moore writes about peonies in her grandparents’ garden, her first grade school teacher, a fresh radish from the vegetable patch. It’s life’s ordinary pleasures that appear to bring her joy. Even while travelling in Greece or Turkey, Mary Ann notes the oregano on feta, a circle of women telling stories. There is a spiritual aspect – the muezzin’s call to prayer, the sanctity of the Hagia Sophia, the sarcophagus of the poet Rumi with its gold Arabic calligraphy. [Photo of crewel work by my mother, Billie, with cover of poem called “Women’s Hands.”]

I wrote: Mary Ann Moore writes about peonies in her grandparents’ garden, her first grade school teacher, a fresh radish from the vegetable patch. It’s life’s ordinary pleasures that appear to bring her joy. Even while travelling in Greece or Turkey, Mary Ann notes the oregano on feta, a circle of women telling stories. There is a spiritual aspect – the muezzin’s call to prayer, the sanctity of the Hagia Sophia, the sarcophagus of the poet Rumi with its gold Arabic calligraphy. [Photo of crewel work by my mother, Billie, with cover of poem called “Women’s Hands.”] Mary Ann links the Ottawa Valley to Turkey and includes the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo at times perhaps for her determination to create despite the physical odds against her. Or it may have been her painting that kept Kahlo alive and Mary Ann reflects on the creativity of women with her grandmother’s quilt, her crocheted doilies and the work of other women whether in a traditional Greek cloth bag woven in patterns of red or a killim created by village women. [Photo of cloth bags made with images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Frida Kahlo.]

Mary Ann links the Ottawa Valley to Turkey and includes the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo at times perhaps for her determination to create despite the physical odds against her. Or it may have been her painting that kept Kahlo alive and Mary Ann reflects on the creativity of women with her grandmother’s quilt, her crocheted doilies and the work of other women whether in a traditional Greek cloth bag woven in patterns of red or a killim created by village women. [Photo of cloth bags made with images of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Frida Kahlo.] The beauty of everyday objects, her relationship with the plant world and to her ancestors, connects this writer to a magnificent spiritual system. [Photo of detail of Turkish, hand painted plate.]

The beauty of everyday objects, her relationship with the plant world and to her ancestors, connects this writer to a magnificent spiritual system. [Photo of detail of Turkish, hand painted plate.]

It’s spring here on Vancouver Island with crocus, daffodils, primulas, hellebores and other colourful flowers in bloom. Winter was a challenge as we had more snow than usual (and we’re not prepared for that out here) and Sarah and I learned in December that the house in which we’d rented the upper level for seventeen years was being sold.

It’s spring here on Vancouver Island with crocus, daffodils, primulas, hellebores and other colourful flowers in bloom. Winter was a challenge as we had more snow than usual (and we’re not prepared for that out here) and Sarah and I learned in December that the house in which we’d rented the upper level for seventeen years was being sold. As I unpacked the linen closet items, I came across a quilt my grandmother made with other quilters in the 1950s. They sat around a quilting frame, sharing stories as they pieced and stitched.

As I unpacked the linen closet items, I came across a quilt my grandmother made with other quilters in the 1950s. They sat around a quilting frame, sharing stories as they pieced and stitched.

As several of us have discovered, we can connect to one another by sharing our stories by email. For those of you not able to attend a Nanaimo writing circle, I’m offering a circle “from away” via email called “Our Stories and How They Connect Us.” It begins Thursday, March 24.

As several of us have discovered, we can connect to one another by sharing our stories by email. For those of you not able to attend a Nanaimo writing circle, I’m offering a circle “from away” via email called “Our Stories and How They Connect Us.” It begins Thursday, March 24. We arrived in Nanaimo, B.C. from Guelph, Ontario with our four cats in May of 2005. We had a few suitcases with us but that was it until our furniture and other belongings arrived about a week later. Life was very simple with so few belongings. Our landlord Peter loaned us laundry baskets full of linens, a mattress, a lamp, dishes and cutlery. I can’t imagine now being without my computer for a week! Sarah painted the bedrooms and we’d take little jaunts out to get to know our new city. Neck Point, just seven minutes from our home, was a favourite spot where we looked towards the Sunshine Coast of the mainland.

We arrived in Nanaimo, B.C. from Guelph, Ontario with our four cats in May of 2005. We had a few suitcases with us but that was it until our furniture and other belongings arrived about a week later. Life was very simple with so few belongings. Our landlord Peter loaned us laundry baskets full of linens, a mattress, a lamp, dishes and cutlery. I can’t imagine now being without my computer for a week! Sarah painted the bedrooms and we’d take little jaunts out to get to know our new city. Neck Point, just seven minutes from our home, was a favourite spot where we looked towards the Sunshine Coast of the mainland. The four cats we brought with us have all died: Miss Pooh, Kadi, Simon and Qwinn. We’re leaving their ashes here, in the Zen garden at the top of the driveway, and their spirits are always with us so they’ll be coming along to our new home in the country. And we’ll be taking Squeaker and Izzy with us, both very much alive. And so far, weathering the transition very well.

The four cats we brought with us have all died: Miss Pooh, Kadi, Simon and Qwinn. We’re leaving their ashes here, in the Zen garden at the top of the driveway, and their spirits are always with us so they’ll be coming along to our new home in the country. And we’ll be taking Squeaker and Izzy with us, both very much alive. And so far, weathering the transition very well. I appreciated WordStorm monthly poetry events in Nanaimo co-founded by David Fraser and Cindy Shantz. I joined a group with them and other writers, calling ourselves the Easy Writers. We had such fun going to Poetry Gabriola as a group meeting the likes of Robert Priest, Richard Van Camp, Ivan Coyote and Sheri-D Wilson.

I appreciated WordStorm monthly poetry events in Nanaimo co-founded by David Fraser and Cindy Shantz. I joined a group with them and other writers, calling ourselves the Easy Writers. We had such fun going to Poetry Gabriola as a group meeting the likes of Robert Priest, Richard Van Camp, Ivan Coyote and Sheri-D Wilson. I made flower essences in the garden here starting with Rhododendron, the definition of which is Self-Trust. Spirit of the Island is the name of the flower essence series, a name Sarah and I came up with together. Another of the Spirit of the Island flower essences is Camellia: Be Here Now. It is a photo of the camellia that attracted our new landlord to read Sarah’s post re looking for a place to live.

I made flower essences in the garden here starting with Rhododendron, the definition of which is Self-Trust. Spirit of the Island is the name of the flower essence series, a name Sarah and I came up with together. Another of the Spirit of the Island flower essences is Camellia: Be Here Now. It is a photo of the camellia that attracted our new landlord to read Sarah’s post re looking for a place to live.