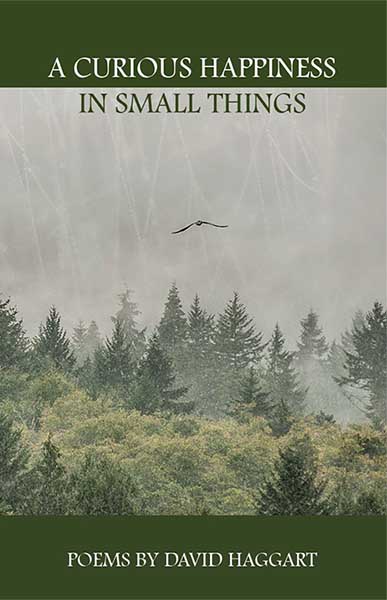

A Curious Happiness in Small Things

A Curious Happiness in Small Things (Raven Chapbooks, 2020) – such a perfect title for a book of poetry, especially this book of praise poems by David Haggart.

The poem from which the book takes its title is about the narrator’s ride in the back of a pick-up driven by a woman “near eighty” down the hill on Mt Maxwell Road. Mount Maxwell is on Salt Spring Island, B.C. where David has lived since 2000.

Happiness in small things appears in other poems in the collection too such as “The Truce” about a boy and his Nanny which ends:

I have learned to be grateful

for the least bit of light.

“Moments in Time” describes some natural wonders such as “a polar bear out on the sea ice,” “caribou heading north,” and “a couple of deer delicately picking / their way through a meadow” and ends with:

And last night —

the first adult conversation you have ever had

with your seventeen-year-old granddaughter

how all of this matters

how it all belongs.

There is little punctuation in David’s poems beyond the odd em dash (in place of a comma) and periods at the ends of stanzas. And that works well! One line leads to another, one poems leads to another. As Robert Hilles wrote in his cover endorsement: “Like all great poetry books, you can’t read just one of these poems. You will be drawn in by the compassion and wisdom and after every poem you will want to pause and reflect.”

David’s “wonderful” daughter, Rebecca Hendry, wrote the beautiful preface to the book. She writes: “In this book you will find love songs to his family, to the glory of nature, and to the fierce beauty of the North. You will find fragments of the incredible and the mundane, the mighty and the fragile, and the healing and the trauma that make up our experience as humans.”

Never mind accolades from people we don’t know, it’s the people closest to us who read and appreciate our poems that matters the most.

In his poem “Giants,” David pays tribute to various poets including Bly, Cohen, Atwood, MacEwen, Oliver, Carver and Patrick Lane “who always breaks my heart.”

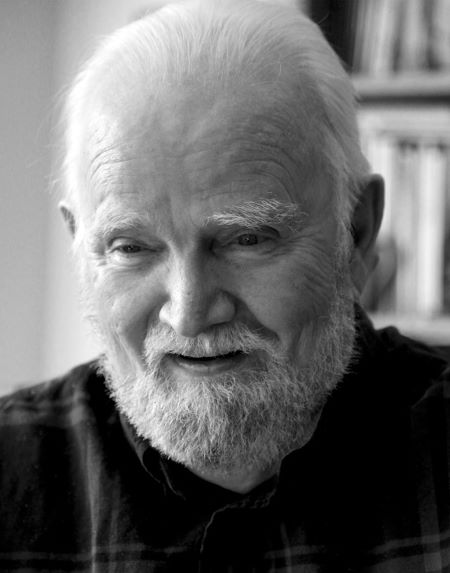

David Haggart was born in 1949 in Brockville, Ontario. He studied journalism in Toronto and worked all over Canada “from cutting pulp in Nova Scotia to working in the bush in the Arctic, spending a fair amount of time in the Barren Lands – savouring the emptiness there.”

David Haggart was born in 1949 in Brockville, Ontario. He studied journalism in Toronto and worked all over Canada “from cutting pulp in Nova Scotia to working in the bush in the Arctic, spending a fair amount of time in the Barren Lands – savouring the emptiness there.”

He moved to the Fraser Valley, B.C. in 1983 working construction and silviculture there. In 1988, David successfully “quelled” his lengthy battle with alcoholism only to discover he had “serious mental health issues.”

In the mid nineties, David began to write and attended a Patrick Lane poetry workshop in Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia. As poet and mentor Patrick advised, David learned to write “by writing.”

David makes note of that advice in his poem “Lane” written after Patrick died in 2019. In the poem, David says following the workshop, he sent “a handful of new poems” and “a copy of a chapbook / I had just published” to Patrick. David writes:

In the letter

I said my only wish

was to write

three beautiful lines

before I died.

He wrote back

lauding the chapbook

with the faint praise it deserved

telling me I had already written the lines

and quoted them back to me —

I have never received a greater gift.

I can appreciate David’s feeling of having received a great gift from his poetry mentor, master poet and teacher Patrick Lane. As the poem was published in recent years and the praise goes back twenty-five years, such a gift has been long lived.

At a gathering on Salt Spring Island recently at the home of Diana Hayes, a poet, photographer and David’s publisher, David read his poem “The Weekend.” It mentions Patrick Lane, also a mentor of mine, and other poets the poem’s narrator will read. The first lines of the first four stanzas are inviting writing prompts I think:

There are things I cannot do . . .

I would give one year of my life . . .

I would like to sing like . .

I would like to find . . .

There are ordinary tasks described (returning books to the library) with a poet’s reflection. The final lines are:

on Monday I will visit a dying man in the hospital

and then go to see my shrink as usual

and read him this poem.

I loved the poem when I heard David read it and love it even more now. As David’s daughter Rebecca says in the preface: “He can hold his sadness close to him, cradle it, turn it over, and look for whys, and yet can be overcome by joy while having a simple meal at a restaurant with his grandchildren where, for a few moments, the light eclipses the darkness.”

A beloved daughter, a respected mentor, a “gifted” psychiatrist have all helped encourage David Haggart’s poems. And as he says in the Acknowledgments: “Thank you also to my publisher, Diana Hayes, without whom there literally would be no book.” Diana Hayes is the publisher of Raven Chapbooks. I thank Diana too for making David’s poems available for many others to read. (David Haggart’s photo is by Diana Hayes.)

Raven Chapbooks is an independent press located on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, founded by Diana Hayes. This family venture first began in the late 1990s as Rainbow Publishers. The press has now turned its focus to poetry chapbooks featuring emerging and established British Columbia poets. A Curious Happiness in Small Things by David Haggart was the first chapbook published by Raven Chapbooks in 2020. To order a copy ($18.), here’s a link to the contact page for Raven Chapbooks: https://www.ravenchapbooks.ca/contact/

Summer, a time of year with little or no structure . . . a free-floating time of musing, pondering and shifting. It’s also a perfect chance to take a “time out” to connect to oneself while being in the nurturing company of other writers.

Summer, a time of year with little or no structure . . . a free-floating time of musing, pondering and shifting. It’s also a perfect chance to take a “time out” to connect to oneself while being in the nurturing company of other writers. A Cabinet of Curiosities

A Cabinet of Curiosities Maps of the Possible

Maps of the Possible Desire Lines & A Memory Map

Desire Lines & A Memory Map In the Writing Life Circle we write from our lives and create writing lives. We write for the love of it. I offer inspiring readings, poems and prompts as doorways to our own stories and “your own way of looking at things.” Much of our inspiration and creative stimulation comes from one another as well as from the work of other writers. There’s no critiquing and no previous writing experience is necessary. Responses to one another’s writing is meant to encourage and support.

In the Writing Life Circle we write from our lives and create writing lives. We write for the love of it. I offer inspiring readings, poems and prompts as doorways to our own stories and “your own way of looking at things.” Much of our inspiration and creative stimulation comes from one another as well as from the work of other writers. There’s no critiquing and no previous writing experience is necessary. Responses to one another’s writing is meant to encourage and support.

MJ Burrows, Marlene Dean and I began the celebrations of our new chapbooks with a salon at Sarah’s and my home which we call The Literary Hummingbird Ranch. Women from the Writing Life circle attended and MJ, Marlene and I were happy to share our poems with women we had spent time writing with and with whom we have shared encouragement and support.

MJ Burrows, Marlene Dean and I began the celebrations of our new chapbooks with a salon at Sarah’s and my home which we call The Literary Hummingbird Ranch. Women from the Writing Life circle attended and MJ, Marlene and I were happy to share our poems with women we had spent time writing with and with whom we have shared encouragement and support.

Writing as a Spiritual Practice: Your Own Tea House Practice

Writing as a Spiritual Practice: Your Own Tea House Practice Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey

Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey Writing Life: A Whole Life Practice

Writing Life: A Whole Life Practice

At this time, more than thirty years later, I’m reflecting on the final chapter of Hagitude: “The Valley of the Shadow of Death.” Dr. Blackie says she had never been “particularly preoccupied by death. Not until now.”

At this time, more than thirty years later, I’m reflecting on the final chapter of Hagitude: “The Valley of the Shadow of Death.” Dr. Blackie says she had never been “particularly preoccupied by death. Not until now.” At the end of the “brutal but restorative treatment,” Dr. Blackie had new insight and had reacquainted herself with delight, “with the pleasure of time and space to simply be.”

At the end of the “brutal but restorative treatment,” Dr. Blackie had new insight and had reacquainted herself with delight, “with the pleasure of time and space to simply be.”