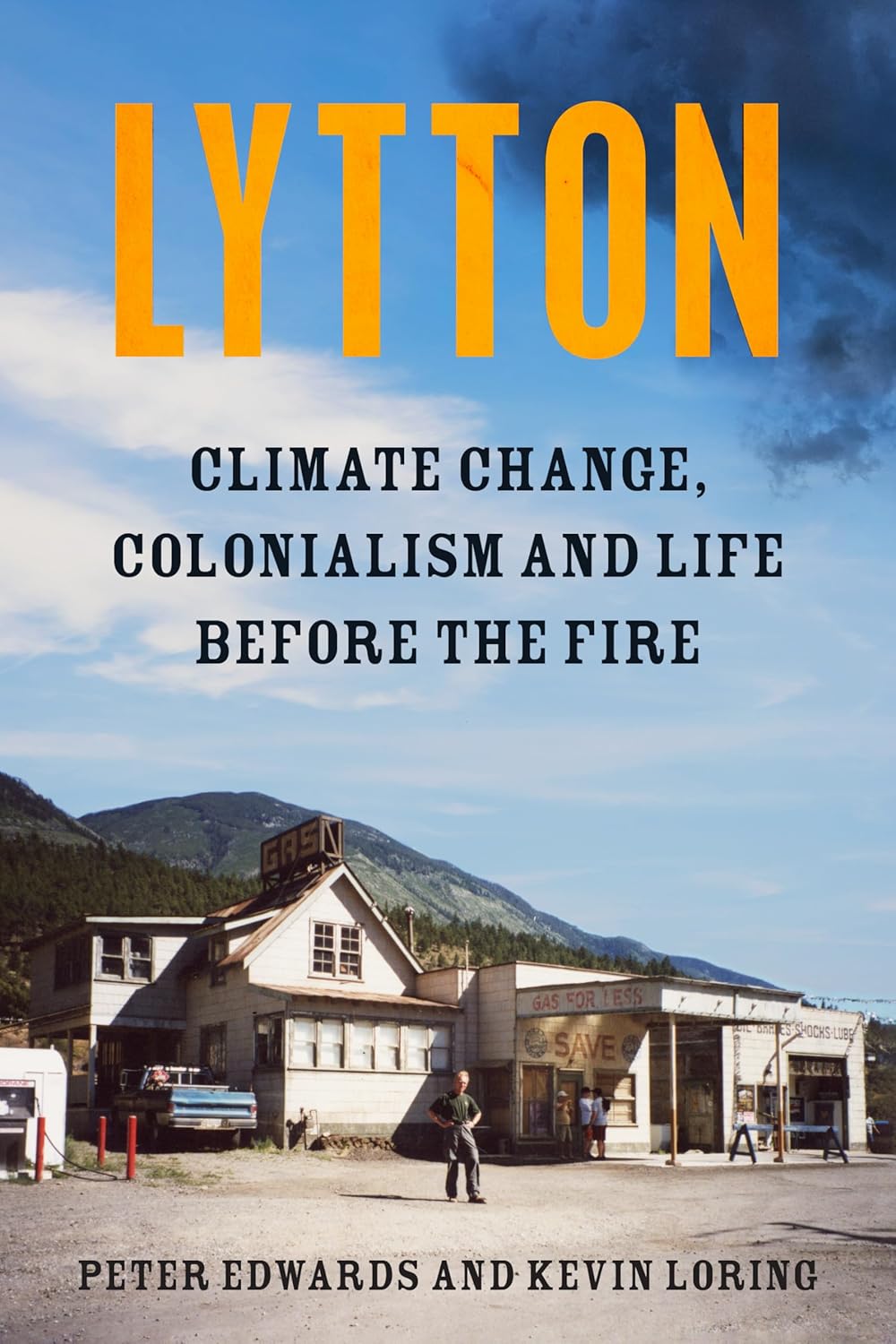

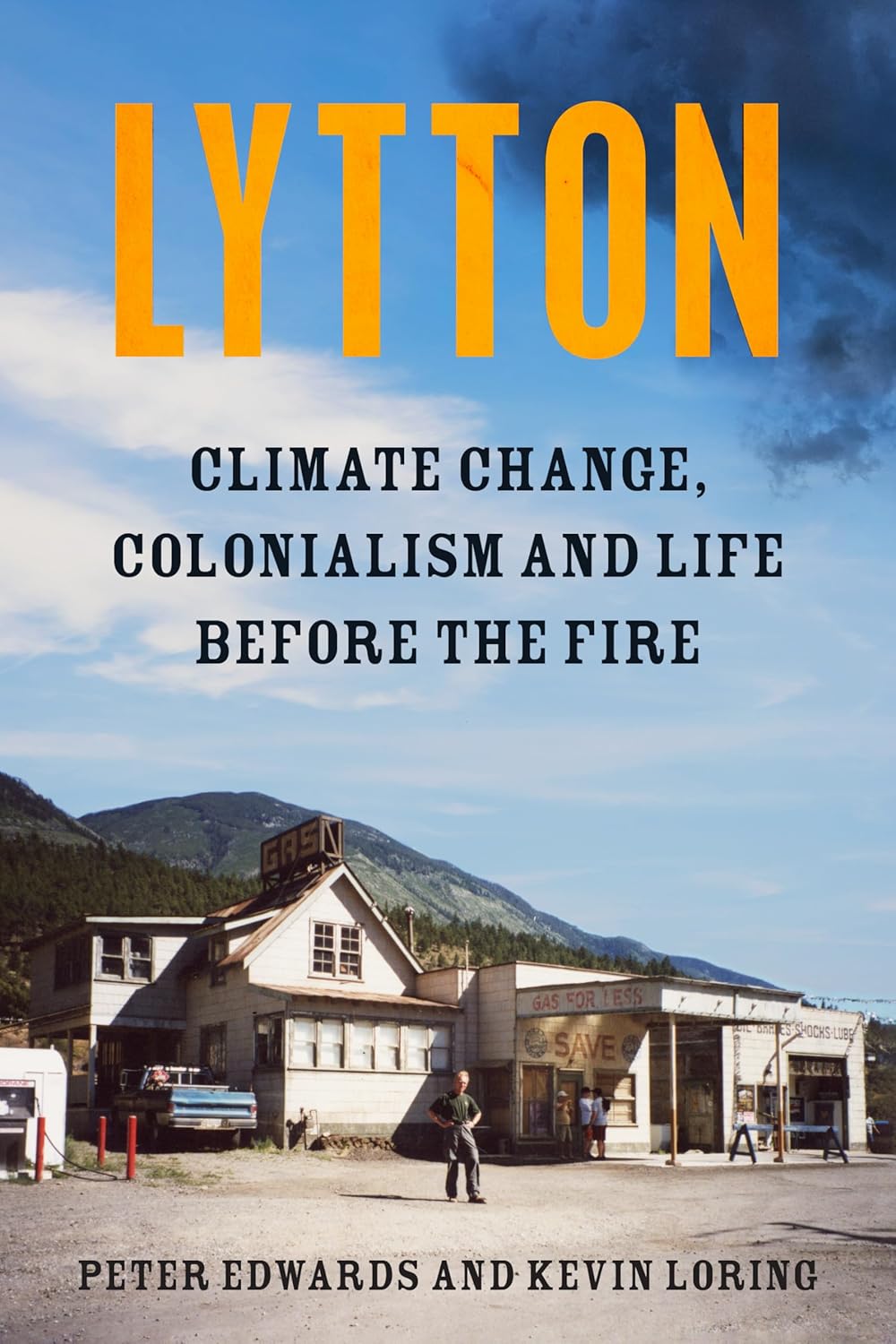

The authors of Lytton: Climate Change, Colonialism and Life Before the Fire (Penguin Random House, 2024) have written a beautifully readable history of the town that holds many fond memories for them. There are probably many who didn’t know of British Columbia’s hot spot, where the Fraser and Thompson Rivers meet, until they heard of the devastating wildfire in June 2021 that burned Lytton to the ground.

The authors of Lytton: Climate Change, Colonialism and Life Before the Fire (Penguin Random House, 2024) have written a beautifully readable history of the town that holds many fond memories for them. There are probably many who didn’t know of British Columbia’s hot spot, where the Fraser and Thompson Rivers meet, until they heard of the devastating wildfire in June 2021 that burned Lytton to the ground.

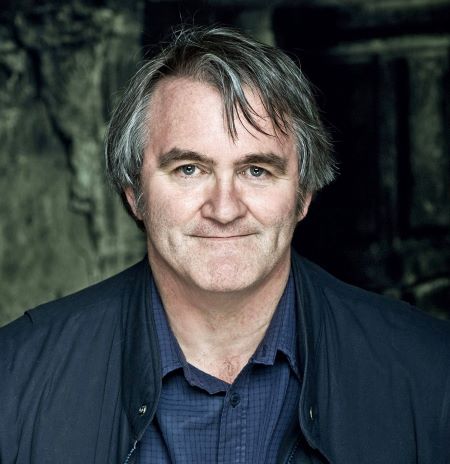

Peter Edwards, organized-crime journalist and author of seventeen non-fiction books, spent his childhood in Lytton. Although only about 500 people lived in Lytton, Peter liked to joke “that he was the second best writer to come from his tiny hometown.” As he says: “We were unaware as children of the horrors that existed for other children who were starting their lives nearby. We almost never saw any kids from St. George’s Residential School, set on farmland just four kilometres from my home.”

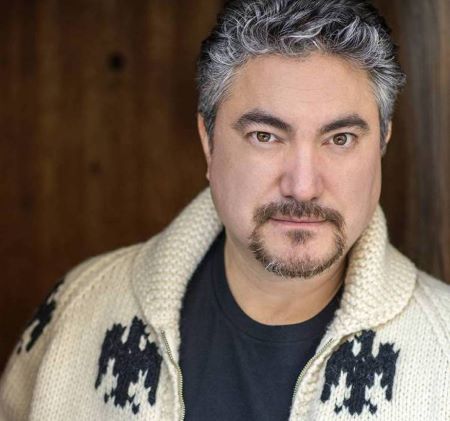

Co-author Kevin Loring, a Nlaka’pamux from Lytton First Nation, grew up to be a Governor General’s Award-winning playwright. He comes from the Loring family from Botanie Valley and the Adams of Snake Flat. As he says, “Lytton is about the size of a city block. The rez at the end of town makes it feel a bit bigger, but not by much.”

“The story of this special place at the heart of the Nlaka’pamux Nation is many thousands of years old,” Kevin writes. His family comes from the early settlers who arrived during the gold rush and the Nlaka’pamux, “who have always called this place home.” His people called Lytton, ItKumcheen, “meaning, in essence, ‘where the rivers meet’ or, as I was told, ‘the place inside the heart where the blood mixes’.”

The name Lytton was chosen by Sir James Douglas out of respect for his boss Dr. Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton, Secretary of State for the Colonies. Bulwer-Lytton was the author of the infamous line: “It was a dark and stormy night.”

Newly arrived Americans during the gold rush which jeopardized the Nlaka’pamux salmon fishery, used the name “The Forks” among others rather than ItKumcheen.

“This place that had been the centre of the Nlaka’pamux universe for millennia was changing, much too quickly for the liking of Chief Cexpen’nthlEm.” He became Chief of the Nlaka’pamux in 1850 and was “at the peak of his influence in 1858.”

Peter Edwards / Photo by Denise Grant

Peter Edwards / Photo by Denise Grant

Rather than strictly chronological, the book’s forty-one chapters focus on themes such as Gold Fever, Promise of Railway, Residential School Revelations, Battle for the Stein Valley, and Climate Change. Interspersed throughout are Peter Edwards’ and Kevin Loring’s memories of this special place.

While the book describes serious themes such as the environment, the legacy of colonialism and Indigenous rights, the authors want readers “to be moved to laugh and cry and appreciate a community worthy of your attention.” Indeed, the book lives up to their intentions.

In the chapter, “Promise of Railway,” the authors write that “Little Lytton soon had its own Chinatown.” First Nations people had guided Chinese prospectors to goldfields during the gold rush so bonds already existed between Chinese and First Nations people when rail workers arrived from China. “More than a thousand Chinese miners may have arrived between 1860 and 1863.”

Chicago engineer and contractor Andrew Onderdonk supervised the construction of 544 kilometres of the transcontinental railway and needed ten thousand men for the job. Two thousand Chinese workers sailed form Hong Kong to Victoria on crowded three-masted ships. Then 6,500 more Chinese workers were brought in and were paid less than half the rate of white workers. They were given the most dangerous jobs and “an estimated four Chinese workers died for each mile of track up the canyon.”

A cantilever bridge was completed in 1882, the first of its kind in North America, “one of the great wonders of the C.P. Railway.” Once construction of the railway was complete, the CPR laid off thousands of Chinese workers. Some moved into caves near neighbouring Spences Bridge and others went to Vancouver. “The 1891 census recorded only twelve Chinese names left in Lytton.”

James Alexander Teit, from the Shetland Islands of Scotland, became an “anthropologist friend” to the Nlaka’pamux and learned to talk with them in their own tongue. To earn a living, he acted as a guide for American and European big-game hunters. One of the expeditions he led was in September 1894 for wealthy Chicago engineer Homer E. Sargeant who began to fund Teit’s research and did so until Teit’s death in 1922.

Teit became involved with helping First Nations leaders protect their land and “distilled the intentions, grievances and concerns of the gathered Indigenous leaders into a document now known as the Laurier Memorial.” The leaders had gathered for two weeks at Spences Bridge and Teit delivered their message to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier at a campaign stop in Kamloops. An excerpt from the Laurier Memorial begins the chapter “Anthropologist Friend”: “We condemn the whole policy of the BC government towards the Indian tribes of this country as utterly unjust, shameful and blundering in every way.”

Kevin writes that Teit’s field notes about the Nlaka’pamux were instrumental in his journey to understanding his cultural practice and history. “Given the loss of traditional knowledge due to the residential schools, his richly detailed notes remain some of the most important insights to our past that we have. Years later, his work informs my community-based art practice.”

“No group that had arrived in the past century was having more impact than the New England Company,” the authors say in their chapter “Entering the Twentieth Century.” It was Anglican missionaries from the New England Company who set up the Lytton Indian Boys’ Industrial school which would later become known as St. George’s Indian Boys’ School.

Built in 1901, St. George’s became part of the cross-country residential school program “that took more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children from their families, beginning in the 1870s and continuing for more than a century, through to the 1990s.”

Reverend George Ditchman’s “reign of cruelty” ended in May 1911 and with Leonard Dawn installed as the school’s second principal, Indigenous boys still fled the school, the authors say in “Suffering Little Children.”

Girls were transferred from All Hallows’ West in Yale to St. George’s which in 1920 had ninety-five students. The government in Ottawa had passed a residential school policy in 1920 which made attendance compulsory for First Nations children aged seven to fifteen. Reverend Louis Laronde was appointed principal. He would confess to “gross familiarity” with the girls but not for the paternity of a student’s child.

Reverend A. R. Lett arrived at the school in 1923 with his wife (Florence) and baby (Marjorie) “as well as high hopes of cleaning up the ongoing mess.” I have done some research into Adam Ralph Lett as he was my great uncle. In 1994, I visited the site of the former St. George’s Residential School in Lytton (the main building burned down in 1982) and did some research at the Anglican Archives in Kamloops. The book, Lytton, has told me much more about the conditions at the time when Reverend Lett found the students poorly fed and clothed and his wife worked in the school as a matron.

While Lett had some experience with farming and had high hopes for the school and its students, the dorms remained overcrowded with “a moral problem” according to Lett, defective heating and ventilation. A doctor in 1927 reported that “thirteen children had died at St. George’s from flu and mumps and there were numerous cases of tuberculosis.”

in the spring of 1933, Lett suffered a breakdown and continued to live “on nerve pills.” In the winter of 1936–37, 152 students suffered measles and whooping cough. Influenza killed thirteen students “while striking 170 more, as well as eleven staff members and four nurses.”

Lett was replaced in 1942. He lived until 1960 and while he may have had contact with his sister, my maternal grandmother who died in 1957, and perhaps his other sister Cecilia, I never met him. My mother, in 1994 when I planned to go to Lytton (we both lived in Toronto at the time), said she hoped Uncle Adam’s school was one of the “good ones.” There were no good ones.

As The Honourable Murray Sinclair, Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada said in his report that included St. George’s in Lytton: “The government used coercion to get the children into the school – and then failed to protect them from neglect, disease, overwork, and abuse. This was the residential school system in operation.”

In “Residential School Revelations,” the authors tell the horrific story of rape, beatings and torture at the hands of Derek Clarke, a dormitory supervisor, and Anthony William Harding, the principal of St. George’s Residential School. Clarke arrived at the school in November 1965. It was in 1987, that Terry Aleck of the Lytton area told his story of abuse to the local RCMP.

Clarke lived in a room off the dormitory. He inspected the boys after they bathed, had his favourite students come to his room, where he had an extensive record collection, and fondled children under their blankets in the main dormitory.

Clarke’s crimes were not investigated until 1987, fourteen years after he left St. George’s. “His initial conviction was for sexual assaults on seventeen different boys, aged between nine and eleven.” The trial judge concluded that Clarke had committed at least 140 illegal sexual encounters, “adding that the real number might be as high as 700.”

Derek Clarke was sentenced to twelve years in prison with two years added when a character witness reported that her son had been molested too. He went to prison in May 1989 at age fifty-two.

There were those who knew of the abuse and did nothing. One of them was Joe Chute who had been the principal of Lytton Elementary for thirty-five years and another fourteen years as mayor of Lytton. He had been a member of the local Anglican church and his friends included Reverend Harding, principal of St. George’s. He heard accounts directly from the boys who had been victims of abuse and didn’t call the police, the boys’ parents or arrange for any further investigation.

Terry Aleck, “the first of the seven former students who provided accounts of abuse at the hands of Clarke and Harding,” refused to settle out of court. He was “successful” in his pursuit of justice against his abusers, the Anglican Church and the federal government in Aleck et al. v. Clarke et al, 2001 B.C.S.C., 1177. He also wanted an apology “from the guy who runs this country.”

Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized on behalf of Canada, in the House of Commons on June 11, 2008, for the atrocities committed at the residential schools against Indigenous children including those at St. George’s in Lytton.

Kevin Loring / Photo by Ian Redd

Kevin Loring / Photo by Ian Redd

Kevin Loring’s play, Where the Blood Mixes, set in Lytton, deals with the intergenerational trauma from St. George’s Residential school. It premiered on the day of the prime minister’s apology. Terry Aleck has been a mentor to Kevin throughout his life. “His brave work helped open the door for other survivors to share their stories, which ultimately led to the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.”

Terry Coyote Aleck is one of the elders honoured in a documentary film entitled s-yéwyáw / AWAKEN co-written and co-produced by my long-time friend Liz Marshall who was also executive producer, one of the cinematographers and directed the film. (You can livestream the film at Telus Originals or knowledge.ca.)

Ruby Dunstan escaped from St. George’s as a thirteen-year-old as she had been punished for speaking her Indigenous language. She went on to become a social worker and the first female chief of Lytton First Nation. Chief Dunstan successfully fought clear-cut logging in the sacred Stein Valley and “helped set up the band-operated Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux School, serving as school board president.”

The Stein Valley is a sacred place to the Lytton Nlaka’pamux and Mount Currie Lil’wat peoples, “a site of medicine and food gathering, vision seeking and cleansing.” As Chief Ruby Dunstan told the Wilderness Advisory Committee in 1985, “This valley is Indian land.”

“Ever since the gold rush, the Nlaka’pamux have been fighting for sovereignty over their lands, and against colonialism and erasure. When the environmentalists came into the community, they too began to talk as though they had authority over the land and could speak on behalf of the future.”

Whether well-intentioned or not, “Chief Ruby Dunstan made it clear that they were not going to be spoken over by shamas, (a derogatory term for white people).”

Lytton had already been known as “Canada’s hot spot” when it set a new world record on Wednesday, June 30, 2021 of 49.6 C as reported by Environment Canada. It was the highest temperature ever recorded above latitude 45 N.

Lost to the wildfire that had begun on June 17, 2021 with a fire reported seven kilometres south of Lytton, were 124 structures in the village of Lytton and 45 in the adjacent Lytton First Nation as well as 34 nearby rural properties. Ninety percent of the local buildings “had been ruined in a flash.” Jeanette and Michael Chapman who sought safety in a trench on their property, were two fatalities of the fire.

Many people sought refuge in Lytton through the years. As the book describes: “In modern times many outsiders would seek shelter there, often people who just didn’t fit anywhere else and were hoping for a little anonymity in the mountains.” Buddhists set up a temple just outside town as they shared the Nlkaka’pamux view of Lytton as “The Centre of the World.” A year following the devastating fire, the monks from the Lions Gate Buddhist Priory held a memorial for animals lost in the fire.

One of the structures destroyed was the Lytton Chinese History Museum which opened in 2017 by Lorna Fandrick when she discovered a Chinese joss house (temple) had occupied the lot in the past. (The original had been built in 1881.) She wanted to commemorate the work, sacrifices, and contributions made by thousands of Chinese labourers. Most of the 1600 artifacts in the museum were destroyed; a few pottery and ceramic pieces survived.

Fandrick hopes to rebuild the Chinese History Museum. A CBC report said: “She plans to focus the new museum around a digital concept, as she has kept a database of all of the items in the museum.”

Among the photos included in the book is one of Tricia Thorpe and Don Glasgow’s reconstructed house, during construction and at completion. “They’re optimistic that their community is worth rebuilding again.”

The smell of the seasons in the canyon, the wind, the

rivers, the mountains. The sound of the coyotes howling

on the west side on cold winter nights. The rhythm

of the trains rumbling by. The big trucks buzzing by on

the Trans-Canada Highway. I played here, learned here,

loved here. My history is here, on these streets, buried

in this ground.

Kevin Loring

An art exhibit entitled “Threadbare” opened on September 20 at the View Gallery at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo. Connie Michele Morey is an artist who witnessed the ecological loss from the wildfire in Lytton. Her mixed media exhibit includes stitchwork, embroidery, sculpture, photography, stop-motion, and performance. According to a press release, “Threadbare explores the effects of colonial industries on interspecies displacement and ecological loss.”

Morey has been visiting Lytton since 2016 and started her project in a cabin north of town. After Lytton was devastated by wildfire in 2021, Morey returned and took photos that became a basis for her art exhibit.

“The exhibition … consists of 12 bodies of work that navigate the tension between perceptions of interspecies relations as exploitable resources and the longing for familial relations,” the artist said in a press release. “Threadbare” is on until November 1, 2024.

Peter Edwards / Photo by Denise Grant

Peter Edwards / Photo by Denise Grant Kevin Loring / Photo by Ian Redd

Kevin Loring / Photo by Ian Redd

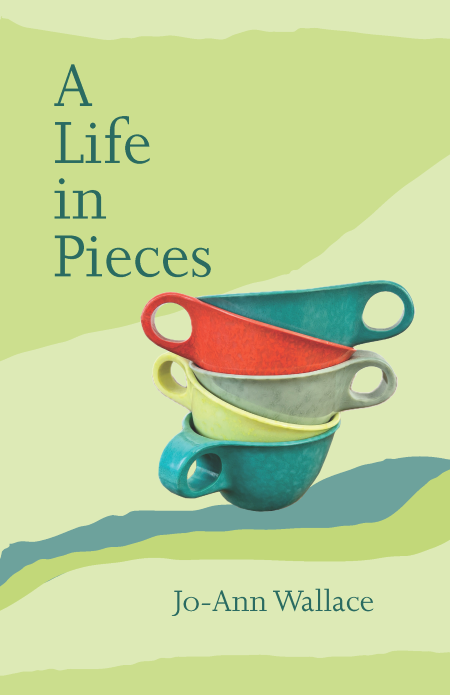

Photo of Jo-Ann Wallace by Stephen Slemon

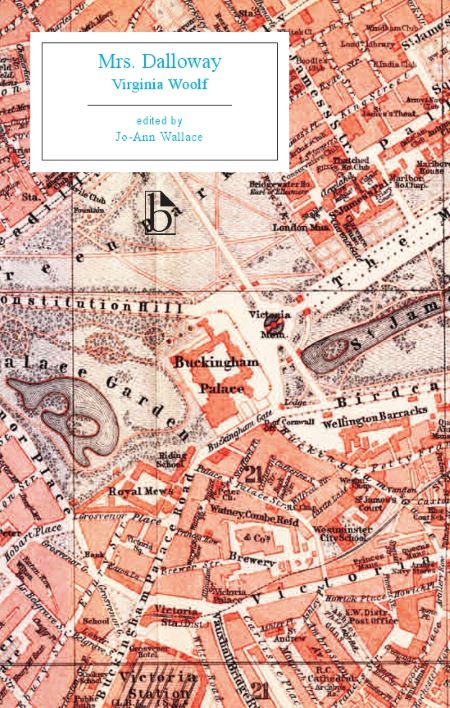

Photo of Jo-Ann Wallace by Stephen Slemon “Mrs. Dalloway has accompanied me through the greater part of my adult life, keeping step with me more than forty years,” Wallace says in “This Gaiety Would Have Been Mine.” The title of the essay is from an exchange between the Woolf characters Clarissa and Peter.

“Mrs. Dalloway has accompanied me through the greater part of my adult life, keeping step with me more than forty years,” Wallace says in “This Gaiety Would Have Been Mine.” The title of the essay is from an exchange between the Woolf characters Clarissa and Peter.