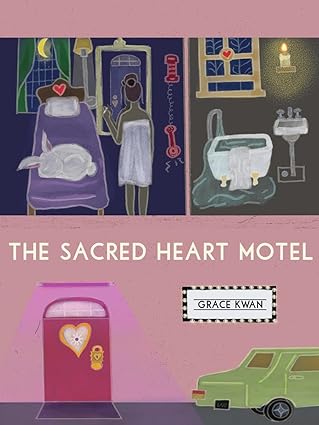

The cover of The Sacred Heart Motel by Niki Hoi (Metonymy Press, 2024) is delightful. The drawings of domestic scenes appear to be done in oil pastel so have a softened effect with rounded edges.

The poems inside Grace Kwan’s (they/them) debut collection are edgier – whether in the kitchen or the areas particular to a motel – rodents die on sticky traps and kitchen knives are dangerous. In “Room 209,” “what’s a love / story without its ghosts – more than a few bullet / wounds in the floor.”

The contents page is a “directory” that includes “The Moonlight Suite,” “Kitchen: Back Exit,” “Next Door, A Bar,” “Room 209,” “Fire Escape,” and “Front Desk.”

One section, “Love, Honour, & Other Stories,” relates to “Dollar bills rescued / from the laundry, numbers kissed / onto napkins,” and other possible objects found in a motel.

Motels are often seedier than hotels and act as places of in between. In Kwan’s case, as a child, in Malaysia’s capital city, Kuala Lumpur, they accompanied their parents to their father’s acting jobs and the family would stay in motels or hotels.

As Kwan said in an interview: “It really always felt very temporary and kind of transient, and I found it hard to pinpoint where I really belonged or what I called home.”

Regarding motels, Kwan said: “I really like their grittiness and that kind of sleaziness – almost kind of dirty . . . It’s not a place that you book in advance; it’s something that you stumble upon in the middle of the night.”

Kwan was working as a server at a hotel restaurant when they started putting the collection of poems together. As they say on their website: “[I] became enamoured with the romance of temporary lodgings as sites where abstract ideas of placelessness, unbelonging, and memory could be situated in space.”

In “Glue Trap,” the domestic scene is a dangerous one – especially for mice. And the speaker’s heart “looks like the old yellow house where thin, mouse-bitten / walls separated our part of the basement from another / Chinese family.”

The poem ends:

. . . . And I can’t deny every time someone tells, confesses,

intimates that they love me, I feel a deep grief ripple

out from inside me – the dearths left by mice

with broken heads and songs unfinished.

In “Gender Studies,” the speaker says:

Beauty was once a country

I belonged to now I’m a migrant

placeless and still hovering

On the limn trying on wages

radium and high heels as a second language .

Kwan says of the poem: “I’m putting the experience of migration alongside the experience of queerness and desire and beauty – and experimenting with how they speak to one another.” While Kwan was writing the poem, they were “thinking of that feeling of transience and not belonging and how that translates into the experience of being queer, and the alienation and isolation that that can bring.”

A knife appears in “Yellow Light” as well as sex in the kitchen. The colours are also of a navel orange, blood, and bodies that are black and blue. You can see Heather O’Neil’s surrealism inspired Kwan’s poems such as this one. Novelist O’Neill is a favorite of Kwan’s who also influenced the title of the book.

In the poem, “The Sacred Heart,” the poet muses: “or maybe a heart’s / a mystery novel.” In the end is the heart:

in communion producing something

quantifiably and qualitatively more magic

than flesh and air.

The hopefulness of the “sacred heart” is at the centre of this splendid collection while the motel opens a door to Grace Kwan’s stunning expressions of longing, melancholy, and the precarious nature of displacement and alienation.

Grace Kwan is a Malaysian-born sociologist and writer based in “Vancouver, British Columbia,” the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. Find them at grckwn.com.