I started to get excited by maps in my first grade classroom when Mrs. Lett pulled down the world map in front of the blackboard and used her pointer to show us where we lived: Eganville, Ontario, Canada. Having seen the many possibilities of personal mapmaking since then, I created a memory map of my childhood backyard. I’m remembering maps sketched on serviettes and discovering ways to explore emotions by mapping them. And I’ve mapped my spiritual journey to Turkey, specifically Catal Hoyuk, an ancient site in central Anatolia, Turkey, which has one of world’s oldest authenticated map.

You Are Here

When my partner Sarah and I sold our house in Guelph, Ontario, she drew a map to show Avril, the new owner, where all the neighbours lived. At a gathering at our home, with the map in one hand, Sarah steered Avril to each neighbour to introduce them and show their position on the map of Kirkland Street. The map viewing began with “you are here.”

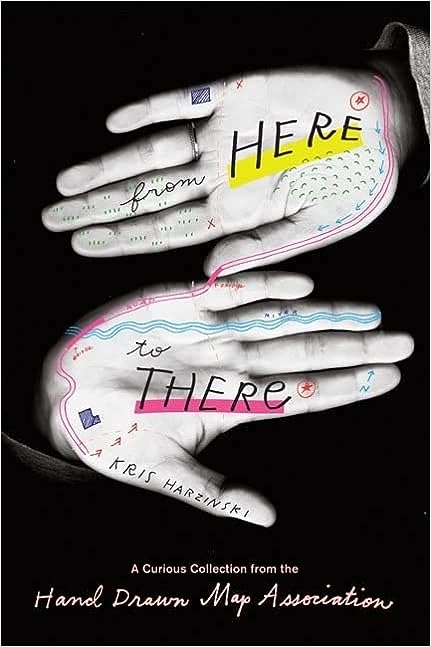

I wonder if Avril kept her hand drawn map or passed it on to the new owners when she sold the house at 38 Kirkland? Through the years I’ve seen many hand drawn maps on the corners of newspapers, on serviettes and on the backs of cigarette package flaps. Although I haven’t kept a collection I was intrigued to see that someone has.

Kris Harzinski began the Hand Drawn Map Association (HDMA), an archive of maps and other diagrams drawn by hand, when he found a collection of maps people had drawn for him over the years. He says in the introduction to his book, From Here to There (Princeton Architectural Press, 2010): “The maps had become much more than useful directions from one place to another; they had become accidental records of a moment in time.”

Kris Harzinski began the Hand Drawn Map Association (HDMA), an archive of maps and other diagrams drawn by hand, when he found a collection of maps people had drawn for him over the years. He says in the introduction to his book, From Here to There (Princeton Architectural Press, 2010): “The maps had become much more than useful directions from one place to another; they had become accidental records of a moment in time.”

Harzinski began to share his maps and to collect maps from others through his website. The hand drawn maps record specific details peculiar or particular to a place. Many are maps of directions. Some are “found” maps while others are fictional such as the one Eleanor Davies created to explain a recurring dream to her friends. She calls her map “Newfoundlands” in which there’s no clear distinction between the land and the water. “In the dream she wanders along the coastline of an island, attempting to reach the beginning, only to find the island is constantly morphing and stretching into a never-ending expanse of land.”

Memory Map

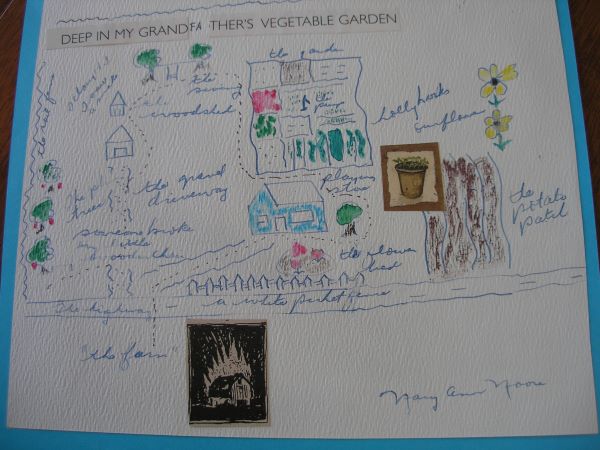

One of the maps I drew some years ago in a women’s writing circle I was facilitating is what I call a memory map inspired by Hannah Hinchman’s book, A Life in Hand: Creating the Illuminated Journal (Gibbs-Smith 1991). Hinchman calls her suggested exercise “memory walking” and I found the not-to-scale drawing to be a pleasant recollection of childhood memories. In fact, the exercise is designed as a happy remembering, not a traumatic one.

The details on the map are meant to be those “your child mind stored away.” Hinchman’s example is a winding line with small illustrations and words along it as she recalled what was significant to her as a child. You don’t need to know how to draw and nothing needs to be to scale.

Drawing my memory map took me back to a time when I became a poet – the solitude, the silence, the development of my imagination. I remembered the stories as I drew the map of my childhood backyard where I lived with my maternal grandparents. The memories all ended up in poems and personal essays.

Beyond the vegetable garden and the pump,

The potato patch and the plum trees,

between the farmers’ wooden fences,

the fields of the valley sing their songs.

From “Ottawa Valley” by Mary Ann Moore included in Those Early Days, Hopeful (Leaf Press, 2010) and Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014).

If I were to tell you about my map, I would say:

The bench under the plum trees is where Grandma and Grandpa sit on warm summer evenings. If you walk across the strip of grass, you come to the gravel driveway that leads to the garage. Grandpa changes his car’s oil filter in there. I play with the stones.

Behind the garage is a woodshed where I play house and behind that, a refuse dump of old tin cans. That’s where I saw a snake one day. At the very bottom of the property looking on to farmers’ fields is a swing.

The vegetable garden, tended by Grandpa, is behind the house. We shared some cucumber there as we sat on the grass and he cut slices off with his pocket knife.

The picnic table behind the house is where I play store with empty boxes and discarded tins. In the winter when a bit of snow mixes with the metal, a particular and strange scent emerges.

Hollyhocks grow up the side of the blue house and sunflowers border the potato patch.

The Third Dimension

Titia Jetten, a Nanaimo artist, who, with her husband Robert Plante, has facilitated workshops called The Map, says: “The interesting thing is that a map is in fact a link between dimensions, because it shows a 3D situation in 2D. The reality around you is translated into a compressed form leaving out one dimension. Every map contains secrets, silent information, because the third dimension is hidden in the second. And when you are a good map reader, you are able to ‘read’ the reality pictured in lines and shapes and colours. Unfortunately people nowadays lose the talent to understand a map, ‘read’ the landscape and decipher the hidden information. They follow the voice in their car and lose every sense of place.”

The Oldest Map

I wonder if the people of the ancient village of Catal Hoyuk in central Anatolia (Turkey) were experiencing a mixture of joy and grief as they depicted everyday rituals and drew a map on a wall in one of their dwellings.

What may be the oldest authenticated map in the world is dated to approximately 6000 BCE and was painted on a wall at Catal Hoyuk. The streets and houses of the Neolithic town are shown in rows lying beneath the profile of the mountain of Hazan Dag. A volcano is part of the wall painting. It was found in 1963 and is now in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey.

In 1998, I was part of a pilgrimage to Turkey called “In the Footsteps of the Goddess.” One of the most significant sites on the tour was Catal Hoyuk. Present day homes in the vicinity are similar to the houses of the ancient site: square with animals roaming around on the flat roofs.

The villagers

of Catal Hoyuk

linked their red ochre handprints

with honeycombs,

painted the palms of others

with seeds

or an egg.

On the eve

of the wedding

in the village of Basmakci,

the women sing,

place a dot of red ochre

on their palms,

the hand of Fatima.

From “Hands” by Mary Ann Moore included in You Are Here (Leaf Press, 2012) and Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014).

Before our tour group went to Catal Hoyuk, we spent the night in private homes in the village of Basmakci where the members of our all-women tour attended a henna party, kina gecesi, where a bride-to-be had her hands hennaed in a special ritual before her wedding the next day.

We also had our hands hennaed so that the next day when we placed our palms on the earth at Catal Hoyuk we were linking our stories, all that we had learned in our modern world, with those hand prints of the people who lived peacefully 8000 years ago. The handprints in red ochre were placed on the walls long before Islam so the hands are as if to say we are here. I have found the symbol of the hand to be an important one to many cultures of the world and a significant connection to one another for thousands of years.

I can’t help but think of the hand prints in dwellings, and on woven rugs for example, as maps of an ancient people. I can look at my own hand and see the past and future there. According to Palmistry or Chiromancy, the “proper” name of divination with the hand, hands tell a tale. There’s a life line, a head line, a heart line and a fate line. All the lines on our dominant hand show us where we’ve been and where we may be headed. A map of lines on our hands that also tell the tale of what our occupation may be whether ink-stained or with gritty nails from garden soil or callused hands from holding instruments.

You Are Here

In one of the women’s writing circles I began to offer in my Toronto living room, we drew our hands noting on them what we wanted to drawn into our lives. I couldn’t help but think then and now of children placing their hands in finger paint and then on a large pieces of paper to create wrinkled artifacts of red hands in a determined row proclaiming: You are here.

“Schedules as little maps of the possible” Sage Cohen said in her book The Productive Writer (Writer’s Digest Books, 2010). With that description schedules have taken on a whole new meaning. I create a list for the day, a sort of map, and look through the window to a fine web of fine grey branches against a November sky. I am reminded of the broken veins on my shins like embroidery – or would a crocheted doily be more apt? I think of the words and write them down as a poem about veins, like branches, on my left leg.

If I could look this close

see the shin etchings

before the surgeon has me

lift my pant leg

to declare calligraphy in blue,

I would see the branches

crocheted across the sky,

the November veil,

trace the tiny crab trail,

through the sand –

a map, shimmering:

you are here.

From “You Are Here” by Mary Ann Moore, is included in You Are Here (Leaf Press, 2012) and Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014).

The Place You Already Are

I find poetry to be a kind of map as well especially since reading an interview with Jane Hirshfield in an interview in Tricycle magazine (Spring 2006). She said: “Poems are maps to the place where you already are.”

Sarah and I have been discovering a new place that reminds me of living in the country with my grandparents. I’m in a different province now and I’m feeling the expansiveness of the property on which we now live in Nanaimo, B.C. We’re very much “here” learning the names of the trees and the wildflowers, the birds and the butterflies. We’re part of a community with the deer, the rabbits and a bear.

When we meander this newly found place, we take careful

steps around randomly placed daffodils, notice tiny white

flowers we haven’t found a name for yet. Josef has made

birdhouses, assembled cocoons for Mason bees. We know

we’ll find our way back to the work we once did.

From “Mending” by Mary Ann Moore included in Mending (house of appleton, 2023)

Mapping Your Spiritual Journey

I’ve written about my pilgrimage to Turkey in Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey and included the memory map I referred to above in a chapter entitled “Memory Walk”. It’s a digital workbook in full-colour, available from the International Association for Journal Writing (iajw.org). Here’s the link for more information and purchasing. Please note prices are in U.S. funds.

I’ve written about my pilgrimage to Turkey in Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey and included the memory map I referred to above in a chapter entitled “Memory Walk”. It’s a digital workbook in full-colour, available from the International Association for Journal Writing (iajw.org). Here’s the link for more information and purchasing. Please note prices are in U.S. funds.